A tragic, but understandable misunderstanding

Misfortune seems to have plagued the police surveillance operation investigating the

Initial media reports indicated that Mr. de Menezes had been “acting suspiciously.” Early news accounts had him attempting to elude police officials by jumping a ticket barrier at Stockwell Underground station, and failing to respond to commands from officials on the scene. A witness reported that the suspect was wearing “…a thick coat that looked padded.” Another claimed he “…appears to have a bomb belt with wires coming out.” Citing witness reports, Reuters said the victim, “…was shot five times in the head after being chased on to an underground train by undercover police.”

Subsequent substantiated reports, however, have established that Mr. de Menezes walked calmly through the subway station, apparently unaware that he was being observed by police. He was apprehended in an underground train and was reportedly being restrained by a police officer when he was killed. The autopsy report cited by the press indicated that Mr. de Menezes was hit in the head by seven bullets fired by

How could an innocent man, looking and behaving normally, be mistaken for a suicide bomber? By what process could a patently false story concerning the circumstances of the shooting materialize?

Some have accused police officials of lying, and of conspiring to cover up the facts surrounding the shooting. Although a police cover-up cannot necessarily be ruled out, an explanation based upon fairly well established psychological principles seems plausible, and possibly sufficient, to explain this unfortunate episode.

According to the British television channel ITV, when de Menezes entered the Metro car, officials "formally identified" him as one of the suspects involved in the suicide bombing attempts of the previous day.

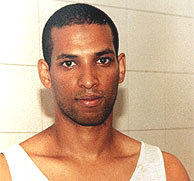

Although Mr. de Menezes had been described by witnesses as “an Asian looking man,” he was, in fact, Brazilian. The actual bombing suspect was Ethiopian-born Hussein Osman. Looking at side-by-side photos of the two men published by news media, it would appear easy to distinguish one from the other. Nevertheless, both men would be recognizable as “foreigners,” not matching the White, Anglo-Saxon stereotype. Both, in other words, were members of an “out-group,” in reference to the stereotypical Londoner.

Although Mr. de Menezes had been described by witnesses as “an Asian looking man,” he was, in fact, Brazilian. The actual bombing suspect was Ethiopian-born Hussein Osman. Looking at side-by-side photos of the two men published by news media, it would appear easy to distinguish one from the other. Nevertheless, both men would be recognizable as “foreigners,” not matching the White, Anglo-Saxon stereotype. Both, in other words, were members of an “out-group,” in reference to the stereotypical Londoner.

It is well established that individuals are better able to visually identify and distinguish between members of their own ethnic group, or “in-group,” as compared to members of ethnic groups to which they do not belong. How often have you heard someone say, “Those (fill in an ethnic group), they all look alike…”? Assuming that the positive identification of Mr. de Menezes was made by native Europeans, under tense conditions, such a mistake seems understandable. I would, however, be surprised if an ethnic Brazilian or Ethiopian would have mistaken one man for the other.

While that might help explain the case of mistaken identity, how do we explain the eyewitness accounts of Mr. de Menezes wearing a bulky coat, a bomb belt with wires coming out, jumping a ticket barrier, etc.?

One’s memories of events are always incomplete, fragmentary. That’s because being human, it is impossible for us to record every aspect of an event the way a camcorder might. One’s attention naturally focuses upon certain aspects of the event more than others. Much important information may go unnoticed, and thus, fail to be encoded into memory.

In addition, our understanding of an event is affected by our knowledge and understanding of similar events. If, for example, I tell you that I had an unpleasant visit to the dentist’s office, you might form an impression of my experience, without my ever having told you specifically what had occurred. Your impression would be a product of your preexisting knowledge and experiences relating to dentist offices. If you later recount the story to someone else, you might contribute new information that was missing from my original account, without even realizing what you are doing. Chances are you would be correct, but you could be wrong. It is quite possible that my unpleasant experience had been an atypical one that you couldn’t have easily imagined.

Psychologists speak of organized sets of beliefs and expectations they call schemas, our existing knowledge frameworks, that influence our interpretation of situations and events. Thus, when our recollections are incomplete, our schemas help us to fill in the missing parts from our store of information concerning similar events.

We all have preexisting ideas about how suicide bombers look, dress, behave, etc. Witnesses recounting their experiences immediately following a subway shooting, in the context of the recent bombings, would be expected to fit their recollections into the general outlines they already have concerning such events, potentially providing faulty eyewitness accounts of the incident. Could this explain why witnesses in the

Other factors potentially adding to the confusion were also in play. Londoners, on the day Mr. de Menezes was shot, were undoubtedly in a heightened state of anxiety and vigilance. It was just two weeks after fifty-two innocent commuters were killed and hundreds injured in four suicide attacks carried out on London’s mass transit system, and one day after multiple suicide attacks were again attempted, albeit, unsuccessfully. Intense emotions like fear, anxiety, shock, and anger can have detrimental effects upon individuals’ perception and interpretation of events, their judgment, and their later recollections of events. Decisions needed to be made quickly. Authorities, we learned, had issued standing “shoot to kill” orders to prevent terrorists from detonating explosive devices while in the process of being apprehended by police.

Knowing what we know about the human propensity for making errors in identifying suspects and recalling events, does it seem reasonable to maintain a “shoot to kill” policy on terror suspects? What about the principle of a suspect being “innocent until proven guilty?” I imagine that controversial police policy will come under intense critical scrutiny during the ensuing investigation.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home